Johnstown Flood

|

| South Fork |

We went to Johnstown to learn about its infamous flood. This turned out to be one of the best daytrips I've ever taken with my son. Johnstown does a really great job of telling its story. While it's a classic tale of the perils of greed, corruption and indifference that transcends time, it's also a tale of pluck and survival in the rebuilding of the town.

We started out where it all began, at the South Fork Hunting and Fishing Club. This is where many of Pittsburgh's wealthiest families liked to summer, in order to escape the dense and unwholesome smog which surrounded the city. Of course many of those same members were the very industrialists who were responsible for the smog. There was no town there; it was a densely wooded area next to a broken dam which had already failed twice, and an empty reservoir. The reservoir once had sluice pipes to control the water level, a control tower and a watchman to insure the water level never got too high. After the dam failed the second time, predictably flooding Johnstown, the sluice pipes were sold for scrap from the empty reservoir and the control tower burned down. Previous floods had made it obvious that the reservoir posed a danger to Johnstown, but both times the reservoir was not completely full so the damage wasn't epic. The club did absolutely nothing to fix the known issues with the dam, they simply patched it up with mud and straw just enough to fill it completely full to create Lake Conemaugh. Without a means to drain the lake, the dam could never be truly repaired. Then they set about weakening the structure further with "improvements" such as fish screens that kept fish in the lake for sport fishing, but also clogged up with debris, and a nice carriage road across the top of the dam that lowered the top by several feet. It had been common knowledge for years that the dam could burst. And then it did, and the results were horrific beyond anything anyone could have imagined. Until September 11, 2001 it was the nation's single deadliest disaster.

The club itself is in pretty awful repair. You might expect that with the Carnegie, Frick, Mellon, and Phipps families, and many other families who were surpassingly rich but less well known today, that the club must have been elegant and luxurious. In fact it was built to be rustic and plain, of inexpensive materials and somewhat careless construction. It was intended only for summer use and had no heating. The 47 rooms were identical and tiny, without electricity, and the building had a two story attached "outhouse". Sixteen of the 66 members had private cottages built on club property so that they would never have to worry about competing for room reservations during busy times. The flood happened in May of 1889 before the club had officially opened for the summer, so the members were not in residence. Without their scenic lake, the club was abandoned and the clubhouse sat vacant for 17 years. Water damage in particular took a heavy toll. The clubhouse was brought back to life by various owners over the decades, but none put serious efforts into restoring it. Now that it is owned by the National Park Service, they are doing all they can to maintain it. They say the very first step is to seal the building so that further water damage can be prevented, and next they need an HVAC system. This would be hugely expensive, and has to happen before any visible improvement to the interior can be made. Otherwise, further restoration is pointless. The Park Service estimates full restoration to cost anywhere from $800,000 to $2,500,000. Ouch! There is some debate about how the building should be restored, and if it should be fully brought back to its days as a clubhouse, or if parts of the building should reflect some of its subsequent history. But all of that presupposes that funds will someday make restoration possible.

Ten of the original sixteen cottages are still standing. They were privately owned, but built on land that was leased from the club. All of the cottages that remain are occupied, although four are actually owned and rented out by the National Park Service. Because they are occupied, they are not open to visitors to tour, and I did not feel comfortable stalking around taking photos!

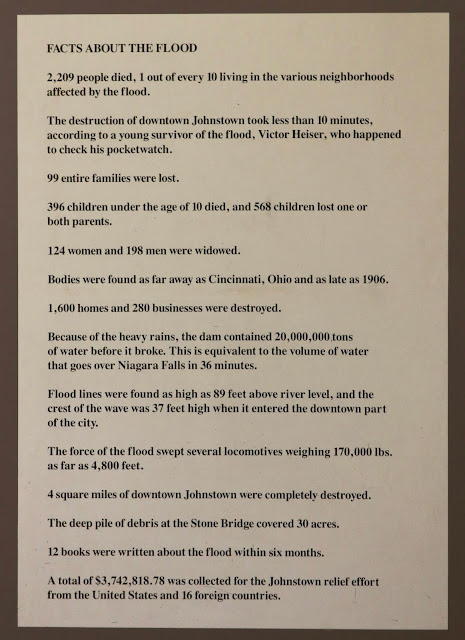

Next we visited the Johnstown Flood Museum. It's operated by the Johnstown Area Heritage Association, and it doesn't pull any punches. The museum does a fabulous job of telling the story of the flood, its devastating impact, and the rallying of the community and the entire nation in recovery and rebuilding efforts. The National Park Service seeks to tell the story of the flood while carefully avoiding blaming anyone. But the Johnstown Flood Museum lays the blame squarely where it belongs, on the negligence of the club. They were the only ones who had any power to prevent the trajedy everyone knew could someday happen. They never took responsibility for their man-made disaster, and successfully fought off all lawsuits that sought to bring some compensation to the survivors whose homes and businesses were utterly destroyed. The town library was not spared in the destruction. It was rebuilt by Andrew Carnegie, and that building now houses the Flood Museum. His club caused a flood that killed 2,209 people outright and caused $17 million in damage (which would be around $463 million today), so he generously gave them one of his new libraries. What a guy.

|

| The model of the city of Johnstown. |

|

| Extensive displays show various items recovered from the debris. Many of them are poignant reminders of ordinary lives cut suddenly short. |

|

| Survivors and journalists sought to tell the story through books and souvenirs. |

|

| Like many Carnegie libraries, this one also functioned as a health club, with a running track above the gymnasium floor. |

We had to take a ride on the gorgeous Johnstown Inclined Plane. It was began a year after the flood in order to serve a new neighborhood being constructed high on the hills, and to create an escape route in case of more floods. It provides a wonderful view of the city, and in addition to passengers it can carry cars! There is a spiffy restaurant at the top, as well as a gift shop that sells ice cream.

We also stopped at Grandview Cemetery to pay our respects to the 777 flood victims whose bodies were never identified. They are buried together in the "Unknown Plot", which serves as a stark visual reminder of some of the human cost of the flood.

Lastly, we returned to where it all began, to the site where the dam once stood. Today there is a valley with the Little Conemaugh River running through it, and an active railroad. Behind this point once stood Lake Conemaugh, more than two miles long. Once the dam failed, there was no going back. Standing here, we got a sense of just how much water that must have been.

Comments

Post a Comment

Hello! I love to read your comments, but please be aware that they are moderated. This will result in a delay before they are posted. Thank you for your patience.